Nashville Veterinary Specialists

Inflammatory Bowel Disease- What is this, really?

Information produced by Julie Stegeman, DVM, DACVIM, Nashville Veterinary Specialists - Clarksville

Inflammatory Bowel Disease (“IBD”), is one of the most common disorders treated by veterinary internists, and yet it is also widely over-diagnosed and misunderstood. The goals of this article are to define what truly composes IBD, what does NOT constitute IBD, and key points in case management.

The World Small Animal Veterinary Association has designated the following criteria in the diagnosis of Idiopathic IBD:

Gastrointestinal symptoms of at least 3 weeks’ duration

Incomplete response to diet change, anthelmintics, antibiotics and symptomatic therapies

Lack of other explanations for the clinical signs

Histologic lesions of significant mucosal inflammation on gastrointestinal biopsies

Clinical response to immunomodulatory medications

Note that in the above criteria, if a pet has a response to diet change or antibiotics, then they are not technically classified as having IBD. These would be classified as Food Responsive Enteropathy or Antibiotic Responsive Enteropathy, respectively.

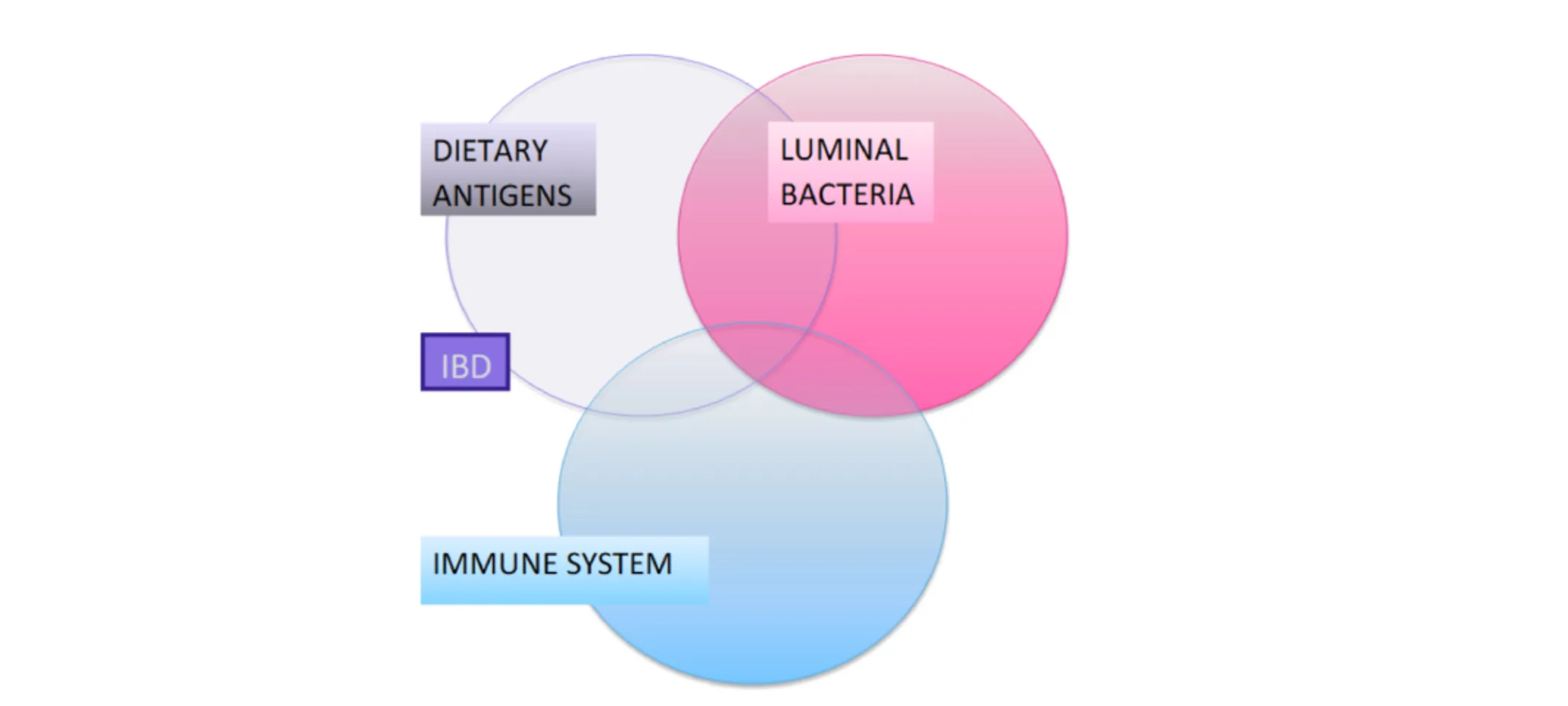

IBD is the result of loss of immunological tolerance to normal luminal antigens, which include dietary and bacterial antigens. When explaining this to clients, I tell them their pet’s immune system is over-reacting to food, bacteria, or both, to such an extent that simply changing the diet and changing the bacteria is not enough, and their pet requires immunosuppressive therapy to achieve control of the condition. That is IN ADDITION TO the diet and bacterial management plan. (Figure 1)

In the initial assessment of a patient with chronic vomiting, diarrhea, and/or weight loss, I first collect a thorough history, and consider age and lifestyle. Are parasites likely? Is there dietary indiscretion? Was there a recent diet change? Is this a senior pet with possible extra-intestinal disease causing the symptoms? A Minimum Data Base (CBC/Chemistry/UA, spec cPL/fPL or PSL, and T4), fecal ova/parasite screen and Giardia antigen are the diagnostic starting point. With chronic diarrhea in young pets I also recommend a fecal pathogen PCR panel to screen for Campylobacter, Salmonella, Cryptosporidium and other protozoal, bacterial or viral pathogens. A resting cortisol level may be appropriate for some dogs as well, to screen for hypoadrenocorticism.

Radiographs of the abdomen +/- thorax may be needed to rule out a foreign body, and to search for neoplasia and other illnesses. Remember heartworm disease can cause vomiting in cats, as can pulmonary neoplasia. Also, not all vomiting is truly vomiting; esophageal lesions will be missed with abdominal radiographs.

Abdominal ultrasound is helpful for localization of the gastrointestinal lesion, and especially helpful to screen for neoplasia or obstructive lesions. It can allow us access to lymph nodes or masses for fine needle aspiration and cytology. Please note that IBD CANNOT BE DIAGNOSED WITH ULTRASOUND. (Figure 2). Changes such as diffuse mucosal thickening can be supportive of a suspicion for IBD, but multiple studies and the author’s own experience do not find a direct correlation of this finding with IBD. Ultrasound has been found to be more useful for assessment of chronic vomiting than chronic diarrhea, and the utility increases with the age of the pet. We generally recommend ultrasound before biopsies, to verify whether endoscopy or surgery is the preferred way to procure those biopsies. If the above assessment has not defined the cause of the symptoms, or has at least ruled out systemic metabolic illness as the cause for the symptoms, then the next step is a diet trial +/- antibacterial trial.

Diet Trial

A diet trial needs to be fully explained to clients- ONE NOVEL PROTEIN source and ONE NOVEL CARBOHYDRATE source is ideal. Some practitioners prefer a hydrolyzed protein diet at this stage. Clients often misunderstand how strict they must be with this trial, and often go “off the diet” with treats and with foods in which they hide medications. I have seen many IBD patients whose owners were sabotaging their own efforts by hiding medications in peanut butter, cheese, etc. I also see clients feeding the prescription diet alongside of their original diet, thinking of the diet like a medication instead of as a replacement for their old diet. Clients will want alternatives to this strict diet; I advise them that if their pet is on duck and pea, then the treats can be cooked duck or cooked peas, hydrolyzed treats, or they can bake the canned food to make “cookies”. I do allow use of miniature marshmallows as a “pill pocket”.

The diet trial should be at least 3-4 weeks long, as the effects of the prior diet will take time to resolve. In my experience, if a diet is a definite poor choice for the pet, that will be apparent within 2 weeks as evidenced by worsening of clinical signs or complete lack of any improvement.

Antibiotic Trials

Antibiotic trials tend to have a faster response rate than diet trials, typically within a week, for those that are truly “antibiotic responsive”. These are usually patients with chronic diarrhea, but chronic weight loss can also be from dysbiosis. I prefer to use metronidazole 10 -15mg/kg BID, as it not only provides good suppression of enteric bacteria, but it also mildly suppresses cell-mediated immunity. Due to possible neurologic side effects, some practitioners and clients prefer tylosin. Tylosin is not absorbed systemically and is quite effective in luminal bacterial suppression, but does not provide any immune modulating benefits. I dose tylosin at 10-20 mg/kg BID; it always requires compounding. It can be sprinkled on the food, but has a bitter taste, so I usually use capsules. Amoxicillin is also sometimes a helpful alternative, especially for Clostridial enteritis.

Biopsies

If diet trials, antibiotic trials, and symptomatic therapy fail to alleviate symptoms, gastrointestinal biopsies should be performed. The exception to the rule of first completing diet and antibacterial trials is if the pet has profound hypoproteinemia, or if the pet has stopped eating and is needing hospitalization for their gastrointestinal disease. Those patients are on a more limited time frame. They may need to skip the therapeutic trials and go straight to biopsy acquisition in order to hasten their diagnosis. The goal of biopsies is to verify a diagnosis, and therefore discover how to best treat the pet. Differentials besides IBD may include Helicobacter, pyloric hypertrophy, fungal infection, structural abnormalities such as a polyp or tumor, diffuse neoplasia, or motility disorders without an inflammatory component. Therefore, trial on steroid therapy could actually be either ineffective or possibly worsen the condition if we guess incorrectly that we suspect the pet has IBD. Conversely, a lack of improvement on steroid therapy does not exclude a diagnosis of IBD.

The method of biopsy acquisition has been debated extensively. Surgical biopsies theoretically provide a “gold standard” sample due to the ability to procure full-thickness samples as well as samples of lymph nodes and other organs. I recommend surgical biopsy if there are multiple organs of concern or if the lesions of interest are beyond the limits of reach of the endoscope (i.e. in the jejunum). Surgery is also preferred if the lesion is expected to be deeper than the mucosal layer (i.e serosal or muscularis lesions). If the disease is expected to be primarily mucosal, then endoscopy is appropriate. A relative contraindication to surgery is profound hypoalbuminemia, as healing may be delayed in these patients.

The special case of small cell lymphoma in cats bears mention. This condition is fairly prevalent, increasing in probability in parallel with the cat’s age. It is rare for us to need full thickness biopsy samples to diagnose this condition. Often it is readily apparent on the mucosal biopsy. If there is any question, a clonality analysis of the T cell antigen receptors (“PARR”) can be performed to determine if neoplasia is present. I have seen many patients have equivocal results on surgical biopsies, where PARR was still needed.

I typically collect endoscopic biopsies from upper and lower GI tract (including the ileum) for all cats and any dog with protein losing enteropathy. For chronic vomiting in dogs without diarrhea I tend to just collect duodenal and gastric samples, or just colonic samples for a pet whose only clinical signs are attributed to the colon.

Inflammatory Bowel Disease Subtypes

There are four subtypes of Inflammatory Bowel Disease:

Lymphoplasmacytic: The grand majority of patients have this form. In general, these are treated with immune suppressants, diet change and antibiotics all at the same time.

Eosinophilic: The second most common form. Basically akin to a severe food allergy; Dietary management is key, with immune suppressants being needed as well. Anthelmintics are also usually provided empirically even if parasite screens are negative.

Neutrophilic: This suggests a bacterial cause for the disease process. In these cases, if fecal PCR screen is negative, fecal cultures may be helpful. I generally treat with a combination of fluoroquinolone and either metronidazole or amoxicillin if pathogen testing is not definitive. Immune suppressive therapy needs to be used cautiously in these patients

Granulomatous: The least common but most frustrating subtype. This type of inflammation suggests a higher level pathogen such as fungal disease, protothecosis, or intra-cellular pathogens are present. Fluorescent in situ hybridization (“FISH”) analysis should be submitted to Cornell University to screen for intracellular pathogens, and fungal serology (Pythium, Histoplasmosis, etc) may be indicated. If thoracic radiographs have not been performed to this point, they need to be taken to screen for evidence of infectious disease in the “other half” of the patient.

IBD Treatment

Once a diagnosis of Inflammatory Bowel Disease is in hand, one can feel more confident about proceeding with definitive immune suppressive therapy ALONG WITH dietary and/or antibacterial therapy as indicated by the patient. Sometimes plan A’” doesn’t work well, so a plan “B”, “C” etc may be needed.

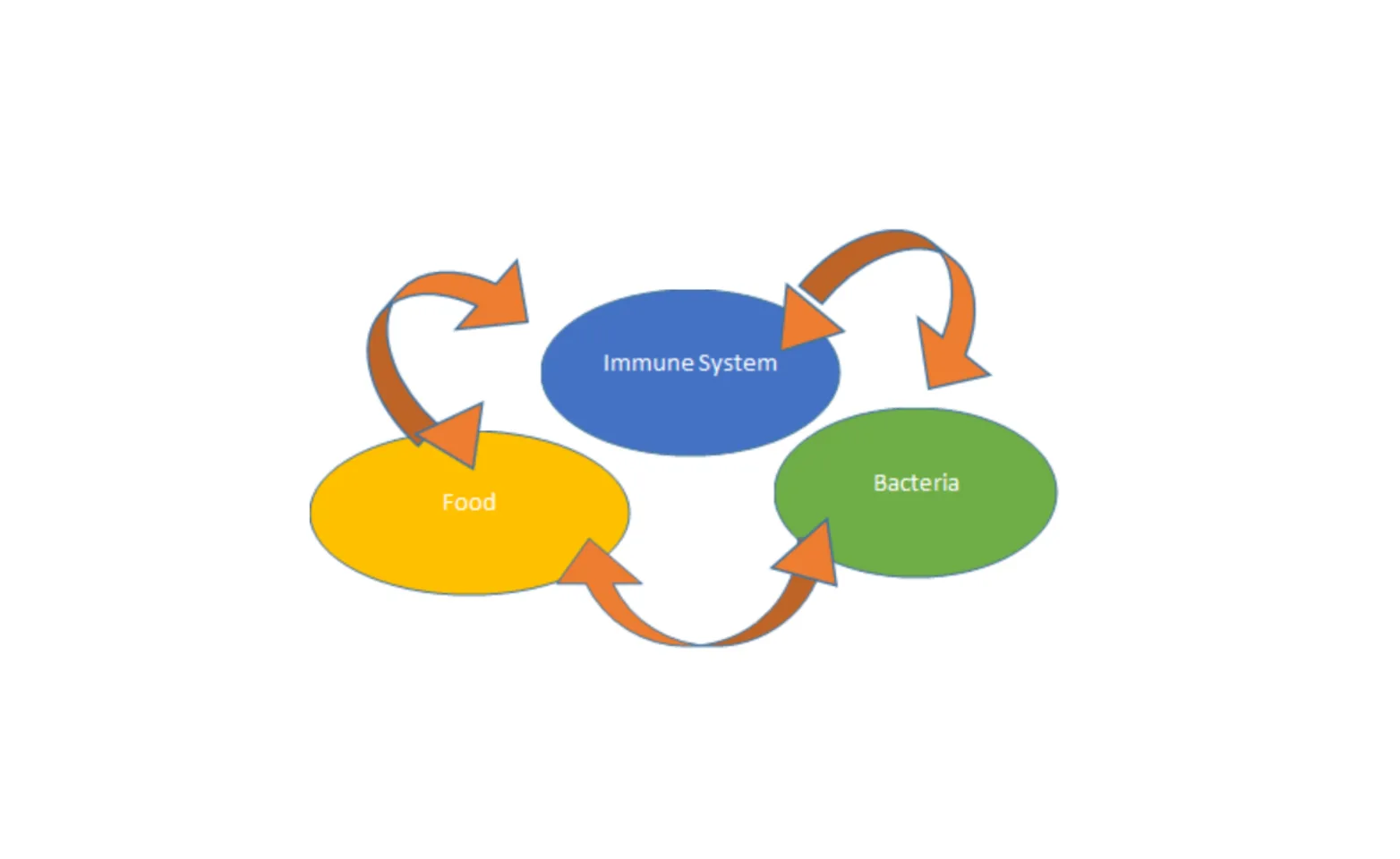

Simply put, we can adjust the diet, the bacteria, or the immune suppressant medications. This trio of therapy is our toolbox with IBD. Clients should be warned that not every pet responds to appropriate therapy right away, and the treatment may need to be altered based on clinical response.

Therapeutic options for IBD constitutes an entire additional article, but a summary is provided in the accompanying table. (Table 1) The patient is usually started on higher doses of medications and tapered over many months. Some pets can be managed long term with just diet after being tapered slowly off the medications. However, repeat biopsies typically still show inflammatory cell infiltrates, which could reactivate if an inciting trigger food or bacteria is presented.

This is a lifelong, treatable but not curable condition which requires good communication with the client and individualized therapy. Prognosis is good to excellent for most cases of IBD. For those with protein losing enteropathy (PLE), prognosis is guarded to fair, as it may be harder to achieve and maintain control. PLE patients usually need life-long immune suppressive therapy but the goal is to have them on every other day glucocorticoid therapy or less.